For the past few months and for different reasons, I have come across an incredible amount of names for ideas that are now trending in Education: Maker Culture, Coding, Deeper Learning, Student Agency, Design Thinking, Formative Assessment, Learning Targets, Student-Inquiry, Project-based Learning, Problem-based Learning, Gamification, Collaborative Work, you name it. So many different ways to say that the focus is now on the students, and on how they learn. What we want with all these “trends” in Education is to innovate, to do better and to do different from the traditional, which now has been demonized as old-fashioned and inefficient, to be erased and forgotten. Although this may be the current narrative – and you all agree with me when I dare say a very lucrative one – we seem to want to do all these “changes” and “innovations” without changing all that much.

The truth is that we know we are not as ready for disruption as we think we are. We want to have students work collaboratively, but they cannot talk too much, or be too loud. We should work on inquiry and project-based learning, but we want to define what students’ projects and driving questions are going to be about. We have to work on students’ socioemotional skills, but this should not interfere too much with their grades. Schools still want to have students ranked by age, classrooms to be rooms with desks and a board, teachers to lecture up front while students listen passively, desks lined up, and multiple choice tests at the end of a pre-determined term. Can you see that the equation doesn’t quite add up?

I read something recently that has really made me reflect deeper upon this frantic situation we are living in. It sort of opened my eyes to the fact that we do not yet know enough about all the new methodologies we are currently trying, at least not enough to say for sure that everything we had been doing is now good for nothing. In a recent interview to Revista Ensino Superior, Swedish professor Inger Enkvist shows concern over all the “big deal” we are making over student-centered methodologies and the so-called innovations in learning. In her opinion, it is too soon to tell whether they are that much more effective than what we have been doing so far, as we lack solid research to measure learning under such approaches, at least over a longer period. In other words, we do not know how well they work, so we might as well begin to measure results and prove they are effective. Even countries that have been often mentioned are innovative, such as Finland, for example, do not have all these changes in place yet.

As an enthusiast of innovative methodologies and student-centered approaches, I must confess I felt slightly offended by her remarks. My first impulse was to think, “oh, great, just another academic who is so wrapped up in her own beliefs that she cannot see that students have changed, and so should the way we teach them”. After reading the interview again, however, I realized that her point was very relevant: we must not forget that learning, knowing, becoming someone who deeply understands something takes hard work, and hard work is not always pleasant, easy, and smooth. Students in Elementary and High School, College, and Graduate Schools need to become life-long learners, but they also need to build method, work ethics, and higher order thinking skills that sometimes take much more than working in groups and doing hands-on, fun activities. Yes, she does have a point.

The same holds true for us teachers. As educators, before going out there claiming that everything we had been doing should now be replaced with “innovation”, we need to know what we are doing, and we must be able to assess and measure results effectively. We have to read more about all the names I mentioned in my opening paragraph, and not just accept a full-day in-service training as the definitive guide to them. We must take a critical stand and be able to assess how these new methodologies are working out in our classroom. We must be bold to try them out, but be ready to go back to basics if that is what our students need in particular situations.

Professor Enkvist goes on to reinforce the idea that we must pursue whatever will bring us good results. If we think about our country (Brazil) and the variety of social classes, living situations, and cultural backgrounds we have, I would say that before prioritizing innovation, we must enable our teachers to hold a decision-making power that only comes with expertise, knowledge, much research, and hard work. In that sense, it is ridiculous, almost naïve to say that students from low-income families struggling with malnutrition, disease, and violence are able to learn in the same way as students from high-tuition private schools, who have access to everything they need to grow up healthy and well fed. It just does not. I am not saying that the first group will not benefit from innovations in learning; the problem is they will need so much more work in order to do the basics that their teachers should be prepared to do what it takes, and not just what is now trending. If we take this to the ELT world, in which CLIL and Bilingual Education seem to slowly become the norm, the gap is even wider. While the principles of CLIL make perfect sense, we know that they are still extremely difficult to apply within the challenging context of many public schools in Brazil.

Finally, I think Ms. Enkvist is right in her concern with the importance of doing what works and also of being a little skeptical of anything that presents itself as the “ultimate solution to learning”. Nothing is that simple. As teachers, we should know better.

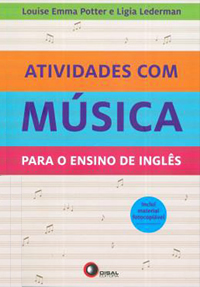

LIVRO RECOMENDADO